I’ve always been fairly prudent with money and recognised its value accordingly. However, through circumstances beyond my choosing or control, I found myself taking out a number of loans in my late teens. While my peers used money from part time jobs for clothes and going out, I was instead supporting my family and now servicing the debt that came with the loans I now had to pay off.

At the same time, my struggle with depression meant I was fully acquainted with the dark cloud that hung over me. I thought the albatross of debt had caused me to feel this way and figured money might be the solution to banishing the immovable cloud that had long plagued me.

Eventually, I came towards the end of the loan and decided to pay it off early. I’d yearned for this day and was sure that I would feel better once I was debt-free. I vividly remember walking into a branch and announcing to the member of staff at the desk that I would like to pay off the balance of my loan. After years of repayments that I resented, this was going to be the beginning of life after debt and I would start feeling better immediately as money was about to solve my problems. Alas, I was wrong.

I walked out of the branch, free of debt, expecting that ominous cloud to have receded as soon as I crossed the threshold of the bank. But it had it hadn’t budged, and it wouldn’t for many subsequent years. I felt helpless and empty. I’d pinned all my hopes of feeling better on paying off my loans but it didn’t change things whatsoever. If anything, it made it worse because I was all out of ideas as to how I would ever address my depression. And I had now succumbed to the belief that I wouldn’t ever be rid of it.

Money couldn’t address my depression, and in effect buy me happiness, and I was ignorant and naive to think it could. Yet in an ever-materialistic society, we’ve been conditioned to believe to the contrary.

When many of us think of happiness, it’s generally linked to an image of materialism. Money and opulent lifestyles produce a narrative for what many of us perceive as a life of happiness. If only we were able to fund that lifestyle, without any constraints, surely our happiness would be secured and guaranteed, right?

We’ve become accustomed to our perception of happiness as a superficial concept. And as a result, we can’t see past or realise our folly in money being a weak, inadequate and hugely misleading gauge by which we measure it.

We can’t pretend that there isn’t a joy and contentment that’s derived from money. Being able to maintain a lifestyle that affords us the freedom to do what we enjoy, and to purchase whatever we desire, without feeling the need to monitor what we’re spending, is undoubtedly what most of us aspire to achieve. And it’s certainly a life I wouldn’t reject.

Although, what happens when we become jaded with what money can provide? When we need to make more and bigger purchases to replenish our levels of happiness? Or when we encounter desires that money can play no role in facilitating, yet run so much deeper than material cravings?

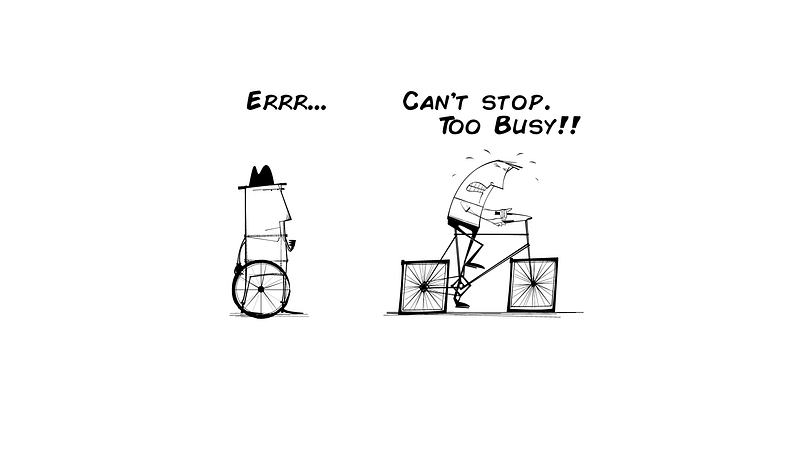

Good health? Companionship? Self-fulfilment? Money can’t buy any of them. It’s at this point that we realise money is a vehicle that will only get us so far in our pursuit of happiness. And like getting on the wrong bus or train, that you were nevertheless sure would get you closer to your destination, it often terminates at a location that makes it even more apparent how far you are from actual happiness.

Bob Marley’s last words to his son Ziggy were “money can’t buy life”. Money wasn’t something Bob Marley was lacking to say the least but he realised that it didn’t buy happiness. Although never more could it have been apparent to him, his family and friends as he died, a rich man who could buy much but couldn’t buy life.

In my lowest periods of depression, no amount of money or material possessions would have been able to shift that dark cloud. Money was a worthless commodity and a currency that wasn’t accepted in exchange for anything that would aid my mental and emotional health improving. Sadly, it’s typically at moments like this when we realise how ineffectual money can be in facilitating our happiness; when we’re already at rock bottom in our distance from achieving it.

It’s difficult to distance ourselves from the notion that money can bring us happiness when we’re bombarded by images that support that. Social media perfectly filters the lives of celebrities appearing ‘happy’ in all that they show us. So we attempt to project our own ‘happiness’ with similarly curated moments that have the same aim of showcasing our materialistic prowess. Because there’s no doubt of someone’s happiness when they’ve taken a selfie of themselves outside of a designer store.

We’ve sadly based happiness on carefully selected snippets from the lives of people we don’t know and assumed that if we had their money, we’d match their assumed happiness too. We don’t know what happens after they put their phones down and aren’t “doing it for the ‘gram”. Are they depressed? Are they experiencing personal problems that make what we see insignificant and shallow in contrast?

Not only are we linking money to a perception of happiness that’s based on someone else’s life, but we don’t even know if they’re actually happy. It begs the question how we’ve been able to make such a strong link between two entities without tangible and credible evidence to support this assumed connection.

How many people underpin their pursuit of happiness by money? Aggressively seeking a partner who’s rich? Or a job with good pay that they hate but feel will validate their self-worth? The assumed feeling of happiness that those decisions result in is typically short-lived as the denial associated with them can rarely remain repressed forever.

Good mental and physical health for ourselves and those around us, self-acceptance and connections to people that matter to us. None can be purchased with money yet all provide happiness to an extent that is unmatched by anything acquired in a store. We need to start redefining what happiness means to us and how we go about achieving it.

Our own path to happiness will always be subjective. Nonetheless, we’ve been made to believe that it’s driven by materialism as capitalism has permeated even how we define good mental health. Hence the narrative of happiness being linked to money. If we consider our own definition of happiness with honesty and introspection, we’ll realise that money isn’t a key to attaining it. It undoubtedly affords us tangible representations that certainly bring us satisfaction and joy. But in the truest sense, money can’t buy us a version of happiness that really matters.

At the same time, my struggle with depression meant I was fully acquainted with the dark cloud that hung over me. I thought the albatross of debt had caused me to feel this way and figured money might be the solution to banishing the immovable cloud that had long plagued me.

Eventually, I came towards the end of the loan and decided to pay it off early. I’d yearned for this day and was sure that I would feel better once I was debt-free. I vividly remember walking into a branch and announcing to the member of staff at the desk that I would like to pay off the balance of my loan. After years of repayments that I resented, this was going to be the beginning of life after debt and I would start feeling better immediately as money was about to solve my problems. Alas, I was wrong.

|

| By Howard Lake and licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0 |

Money couldn’t address my depression, and in effect buy me happiness, and I was ignorant and naive to think it could. Yet in an ever-materialistic society, we’ve been conditioned to believe to the contrary.

When many of us think of happiness, it’s generally linked to an image of materialism. Money and opulent lifestyles produce a narrative for what many of us perceive as a life of happiness. If only we were able to fund that lifestyle, without any constraints, surely our happiness would be secured and guaranteed, right?

We’ve become accustomed to our perception of happiness as a superficial concept. And as a result, we can’t see past or realise our folly in money being a weak, inadequate and hugely misleading gauge by which we measure it.

We can’t pretend that there isn’t a joy and contentment that’s derived from money. Being able to maintain a lifestyle that affords us the freedom to do what we enjoy, and to purchase whatever we desire, without feeling the need to monitor what we’re spending, is undoubtedly what most of us aspire to achieve. And it’s certainly a life I wouldn’t reject.

Although, what happens when we become jaded with what money can provide? When we need to make more and bigger purchases to replenish our levels of happiness? Or when we encounter desires that money can play no role in facilitating, yet run so much deeper than material cravings?

Good health? Companionship? Self-fulfilment? Money can’t buy any of them. It’s at this point that we realise money is a vehicle that will only get us so far in our pursuit of happiness. And like getting on the wrong bus or train, that you were nevertheless sure would get you closer to your destination, it often terminates at a location that makes it even more apparent how far you are from actual happiness.

Bob Marley’s last words to his son Ziggy were “money can’t buy life”. Money wasn’t something Bob Marley was lacking to say the least but he realised that it didn’t buy happiness. Although never more could it have been apparent to him, his family and friends as he died, a rich man who could buy much but couldn’t buy life.

In my lowest periods of depression, no amount of money or material possessions would have been able to shift that dark cloud. Money was a worthless commodity and a currency that wasn’t accepted in exchange for anything that would aid my mental and emotional health improving. Sadly, it’s typically at moments like this when we realise how ineffectual money can be in facilitating our happiness; when we’re already at rock bottom in our distance from achieving it.

It’s difficult to distance ourselves from the notion that money can bring us happiness when we’re bombarded by images that support that. Social media perfectly filters the lives of celebrities appearing ‘happy’ in all that they show us. So we attempt to project our own ‘happiness’ with similarly curated moments that have the same aim of showcasing our materialistic prowess. Because there’s no doubt of someone’s happiness when they’ve taken a selfie of themselves outside of a designer store.

We’ve sadly based happiness on carefully selected snippets from the lives of people we don’t know and assumed that if we had their money, we’d match their assumed happiness too. We don’t know what happens after they put their phones down and aren’t “doing it for the ‘gram”. Are they depressed? Are they experiencing personal problems that make what we see insignificant and shallow in contrast?

Not only are we linking money to a perception of happiness that’s based on someone else’s life, but we don’t even know if they’re actually happy. It begs the question how we’ve been able to make such a strong link between two entities without tangible and credible evidence to support this assumed connection.

How many people underpin their pursuit of happiness by money? Aggressively seeking a partner who’s rich? Or a job with good pay that they hate but feel will validate their self-worth? The assumed feeling of happiness that those decisions result in is typically short-lived as the denial associated with them can rarely remain repressed forever.

Good mental and physical health for ourselves and those around us, self-acceptance and connections to people that matter to us. None can be purchased with money yet all provide happiness to an extent that is unmatched by anything acquired in a store. We need to start redefining what happiness means to us and how we go about achieving it.

Our own path to happiness will always be subjective. Nonetheless, we’ve been made to believe that it’s driven by materialism as capitalism has permeated even how we define good mental health. Hence the narrative of happiness being linked to money. If we consider our own definition of happiness with honesty and introspection, we’ll realise that money isn’t a key to attaining it. It undoubtedly affords us tangible representations that certainly bring us satisfaction and joy. But in the truest sense, money can’t buy us a version of happiness that really matters.